In the complex and interconnected realm of modern operations, the human element plays a pivotal role. In industries ranging from manufacturing and aviation to healthcare and beyond, the potential for human error remains a significant concern. Addressing these errors involves more than correcting immediate mistakes; it requires a deep understanding of their far-reaching side effects. Learning about the side effects of operator errors is critical, as they influence not just the immediate operation but also the broader aspects of safety, efficiency, and organizational credibility.

Understanding Operator Errors

Definition and Types of Operator Errors

Operator errors refer to unintended actions or inactions by individuals responsible for managing equipment or systems, leading to undesired outcomes. These errors generally fall into three categories: skill-based, decision-based, and perceptual. Skill-based errors are routine lapses occurring during familiar tasks, often due to distraction or over-familiarity. Decision errors arise from incorrect choices or judgments, often under pressure or due to inadequate information. Perceptual errors occur when an operator misinterprets sensory information, possibly due to poor environmental conditions or misleading cues.

Factors Contributing to Operator Mistakes

The causes of operator errors are multifaceted, including inadequate training, fatigue, stress, complex or poorly designed systems, and ineffective communication. For instance, in high-pressure environments like air traffic control or emergency medical services, stress and fatigue can significantly impact decision-making abilities. In manufacturing, complex machinery with inadequate ergonomic design can lead to skill-based errors. Understanding these factors is essential for developing effective mitigation strategies.

Consequences of Operator Errors

Impact on Safety

Safety is the most immediate concern regarding operator errors. Mistakes can lead to serious accidents, injuries, or fatalities, particularly in sectors like aviation, healthcare, and industrial operations. For example, in aviation, a pilot’s navigational error could lead to catastrophic consequences. In a healthcare setting, a nurse’s miscalculation in medication dosage can be life-threatening.

Economic and Reputational Repercussions

Beyond safety, operator errors can have significant economic impacts, including costs associated with downtime, repairs, legal liabilities, and compensation. Furthermore, such errors can damage an organization’s reputation, leading to decreased customer trust and potential loss of business. A notable example is the automotive industry, where recalls due to operational mistakes can lead to massive financial losses and tarnished brand images.

Strategies for Minimizing Operator Errors

Effective Training and Education

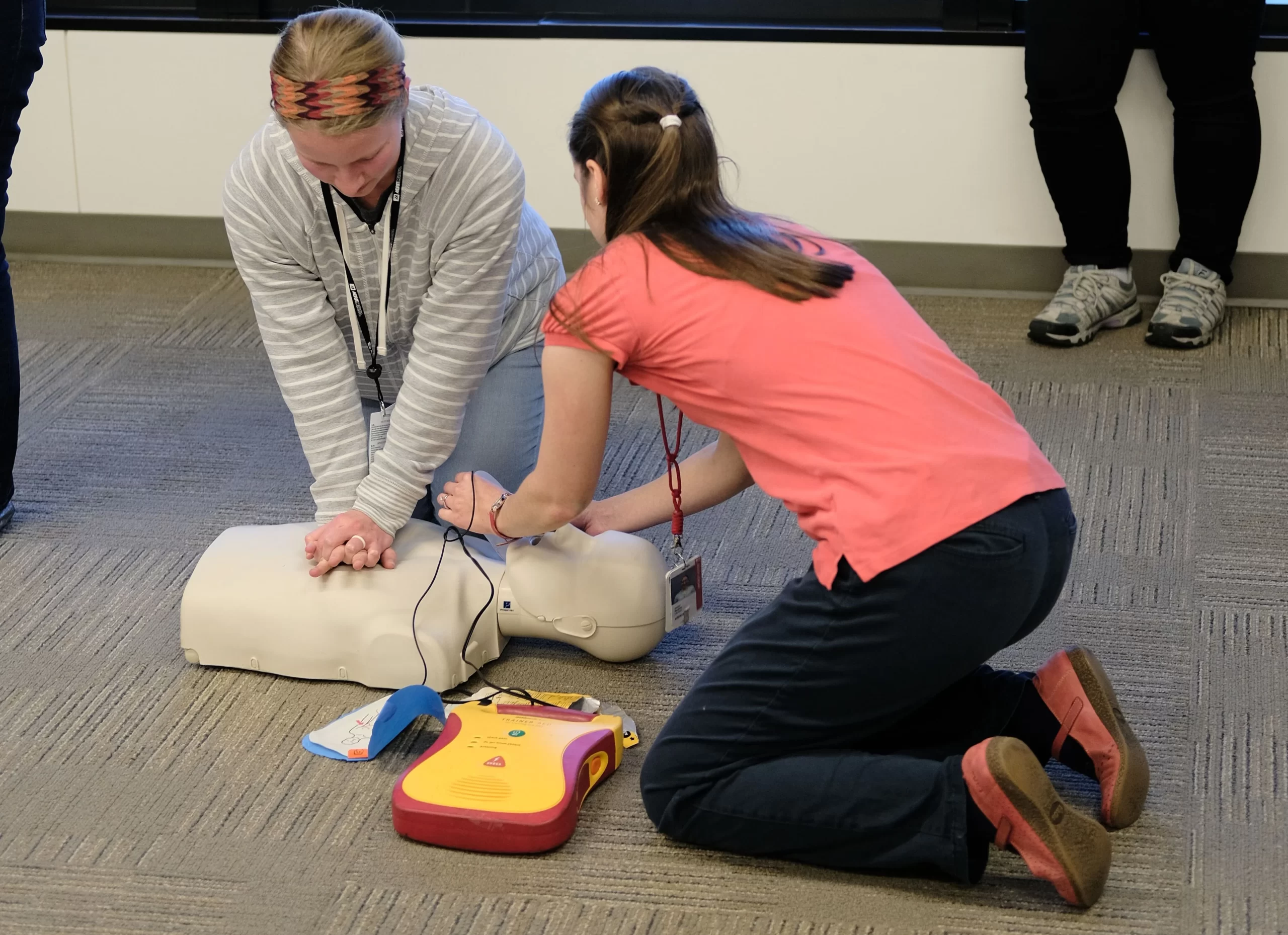

Robust training programs are critical in minimizing errors. This includes not only initial training but also ongoing education to keep skills sharp and updated. Simulation-based training, for instance, has proven effective in fields like aviation and healthcare, providing a risk-free environment to practice and learn from mistakes.

Implementation of Safety Protocols

Safety protocols serve as a blueprint for operators, guiding their actions and decisions. These protocols need to be clear, regularly reviewed, and updated based on new insights and technological advancements. Regular drills and protocol reviews help ensure that safety remains a forefront concern.

Technological Aids and Automated Systems

Integrating advanced technology and automation can support operators, reducing the likelihood of human error. However, it’s crucial to strike a balance, ensuring that technology aids rather than replaces human judgment. For instance, automated monitoring systems in manufacturing can alert operators to potential issues before they escalate.

Case Studies: Learning from Past Mistakes

Historical incidents provide valuable lessons in the consequences of operator errors. The Chernobyl nuclear disaster, largely attributed to operator mistakes and design flaws, underscores the importance of rigorous training and robust safety protocols. Similarly, the Three Mile Island incident highlights the need for clear communication and effective response plans in crisis situations. These case studies emphasize the necessity of learning from past errors to prevent future catastrophes.

Creating a Culture of Safety and Accountability

Promoting Awareness and Responsibility

Cultivating a safety-focused culture is essential. This involves regular training, open discussions about safety, and clear communication of safety standards and expectations. It’s about creating an environment where safety is everyone’s responsibility.

Encouraging Open Communication and Reporting

A culture where operators feel comfortable reporting mistakes or near-misses is vital for continuous improvement. This openness can lead to a better understanding of why errors occur and how to prevent them in the future.

Continuous Improvement and Adaptation

Adapting to new safety standards, learning from mistakes, and continuously seeking improvements are key to minimizing operator errors. Organizations should be dynamic, responsive to change, and always seeking ways to enhance safety and efficiency.

Conclusion

Minimizing operator errors is a complex challenge that requires a comprehensive and proactive approach. From investing in training and safety protocols to fostering a culture of safety and responsibility, every step contributes to enhancing overall safety. By understanding the multifaceted nature of operator errors and their consequences, organizations can not only prevent accidents but also build a more resilient, efficient, and trusted operation.